Imagine my surprise when, going through my grandfather's papers, I saw the familiar street names and realized that he worked at this very factory - and loved telling about this page of his amazing life, how he was making WWII's ikonic PPSh submachine guns even as the city's defenses crumbled and Germans advanced on Moscow's outskirts.

My gramps Karl Pruss wasn't even supposed to be in Russia. He was born in Bern, Switzerland, on May 1 1911. His parents fled political persecution in Russia, but they didn't teach Karl any Russian. He grew up fluent in German and French (after the family moved to Geneva, Karl became Charles Prousse; that's how my grandma called him, "Charles" pronounced the French way). He was about to start his senior year in College Calvin when his mom Genya, against better judgement, decided to spend a year in the old country. Karl's father Wulf Pruss, a watchmaker and a teacher, has already been in Russia, after 20 years of absence, on a temporary job with a crazy American NGO, teaching institutionalized Russian street children how to make watches. After months of separation, Genya was restless and simply didn't think about the risks of getting stuck in Russia... As I am told, Karl would have become eligible for Swiss citizenship after graduation, in a year's time, but an extended stay away from Switzerland could jeopardize it. The school's headmaster loved his talented student and begged Genya to let Karl stay at his place, to continue the studies, and to apply for citizenship, but she wouldn't budge. Well, in Russia, their "Nansen passports" of noncitizens were confiscated, and they never left the USSR again.

There were many bright and funny episodes but even more horrible pages of Karl's 50 years in the USSR. He didn't like to talk about his father's and brother's deaths in Stalin's terror, and even less so, about his own stint in the Gulag, expulsions from schools and jobs... But a story of being a young translator to a group of Francophone foreign Communist cadres, apparently including Comrade Ho Chi Minh, and going with them on a Volga river cruise, with all the funny mishaps, was a favorite.

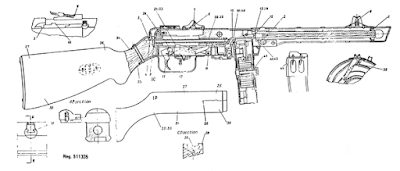

The story about submachine gun production in besieged Moscow was told as a funny vignette, "just imagine, a precision mechanical engineer jerry-rigging production lines to churn out these crudely stamped sheet metal monstrosities!". But even as a kid, I understood that it was not so funny, that everyone believed that the city was destined to fall and its Jewish residents would all be dead. That my dad, just shy of two years old then, has been displaced to the hinterland of Russia and nobody expected the toddler to ever see his father again. I know a lot more poignant and scary context now.

Karl Pruss graduated from the "Moscow Tech", the prestigious Bauman University, from the Precision Mechanics Department organized a decade earlier by his own father. Before his execution, Wolf Pruss managed to build Russia's first watchmaking factories, to hire foreign specialists and to train their domestic replacements. The whole family worked across the giant country at these fledgling plants, which quickly turned into "watchmaking in the name only". The USSR was rapidly militarizing, and almost all the industries were dual-purpose civilian and military production centers. Time fuses, aviation instruments etc. were becoming the main output of the watchmaking factories, and Wolf Pruss's Precision Mechanics Trust was folded into the munitions administration of the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industries. Everything was now defense and classified. Karl's Master's Thesis was on a new design of a recording chronograph, and he seemed destined for military-industrial work.

But the calculus changed when, at 26, he suddenly became a son and a brother of the condemned enemies of the people. With the top-clearance jobs now out of reach, Karl settled for a far less glorious engineering position at SAM, a factory manufacturing mechanical calculators and typewriters. When the Wehrmacht invaded Russia, he was on a launch team of a mechanical cash register production. These decidedly civilian products were being hurriedly replaced by war materiel, and by August 1941, less than two months after the invasion started, SAM started making submachine guns on a trial basis. By then the Germans had already advanced over 300 miles. Karl's aunts and cousins in Belarus were trapped behind the German lines; none will survive the war. Hundreds thousand draft-ineligible men from Moscow were sent to People's Militia divisions to man an additional line of defense around Moscow, just in case the Germans break through. Karl was ordered to keep his job, now deemed too important for the defense effort.

The German breakthrough came in late September. By October 7, both Red Army's forces of the main defense line and the poorly equipped Militia at the 2nd line were encircled. Moscow was just over 100 miles away, with hardly any Red troops left to stop the onslaught. A motley collection of cadets and police forces tried their best to slow down the German war machine, but on October 15 Stalin made a decision to prepare Moscow to surrender. The government, the factories, the research centers were ordered to be relocated East the following day, October 16th, known as Moscow's Black Day. Only Stalin himself and his closest minions, as well as production factories of immediate relevance to the front, were to stay. On the morning of the 16th, the city was in chaos, enveloped by smoke and soot of the burning archives. The subway and the street cars didn't run. People lined up at the factory offices to receive their last pay. Looting started, and the leaflets calling for a pogrom appeared.

Karl's wife, then a grad student, received an order to relocate with her school. By the end of the day, she was with her 1 year old son, my father, in a cattle car of a freight train slowly going East. Karl's SAM factory also received an order to relocate. But not him. The troops on the outskirts of Moscow needed every gun they could get right now, and wouldn't allow the production to be shut even for a few weeks for relocation. The submachine guns were being sent to the front literally as they were being assembled. The logic of the moment was that even if the production line and its workers become a total less with the expected fall of the city in two or three weeks, the guns they produce in the meantime would justify the loss.

Then, a miracle happened. Two days after the Black Day, the fall season arrived in force with torrential rains, turning Russian roads into rivers of mud. By the time the mud froze in two more weeks, the Russians brought in enough reinforcements to save their capital city. And SAM's production, now called Factory #828 of People's Commissariat of Mortar Munitions, started expanding, gradually filling the other buildings left behind by the relocated factory, and then into the buildings of adjacent factories. It was manned by 14, 15 years old boys and by women. The PPSh was a cutting-edge model, just commissioned a year earlier, and the whole 1941 production at all sites amounted to 90 thousand guns. But with the scale-up, they soon made more of these guns in one months. The old SAM remained a bit player. At the height of the production, the 828th was churning out 5,000 guns a month.

But Karl Pruss was stuck at the 828th for 3 more years, all this time resenting the fact that his unique watchmaking engineering skills were being squandered for something as technologically primitive as the PPSh guns. Only in 1944 the factory finally allowed him a job transfer to the National Time Synchronization Service.

And the factory? It shifted into digital calculators, and eventually, into all sorts of military electronic equipment. But it kept on shrinking in the post-Soviet times, and its best buildings are occupied by restaurants and boutiques now. And one venerable tango venue, too.

It may be hard to even conceptualize the role of tango in today's Russia, amidst all the mushrooming hate and the unending war. It is first and foremost an escape, an illusory world away from the daily horrors, a way to keep on pretending that life is whole, unbroken. I needed its embraces for this escape and this illusion, for my sanity. It's a good, positive role in many ways. But it isn't guilt-free, not at all. The government also wants its sheeple to be contented in the same illusion of unbroken life. There are endless celebrations, festivals and talent shows in town, a veritable Feast in the Times of Plague. And tango, perhaps unwittingly, plays along. Perhaps a milonga is more of a simple act of spiritual healing, but what about the performances and the festivals which still go on? Almost all of the showcased talents are local now, but occasional Argentines, like Alejandra Mantignan, come to teach and perform, too, and I find it extremely objectionable. And then, there is no escape from the horrors of the outside world even in the cloistered space of a milonga. People aren't always silent. And they don't always limit their talk to the music and the steps. I haven't heard anything full-bore militantly patriotic; it looks like almost everyone fears the war or hates it. But it isn't so simple. There is a lot of xenophobia directed at the Ukrainians and the West in general, a lot of regime-fanned grievances. They did this to us, they did that to us, we didn't deserve any of it kind of stuff. There is a widespread belief that the Russian forces behave impeccably, never target any civilians, that all the war crimes are either fakes or false-flag operations by the Ukrainians themselves. Occasionally people open out and whisper how they hate Putin, but even then, it's all someone else's fault, not Russia's. I mean, in America we sort of tiptoe around conspiracies and crazy beliefs, be it about politics, vaccines, or some other health and wellness issue. It's happening outside of the ronda, especially in the social networks, and it slowly poisons our pure world of dance and music from the outside, but sometimes it invades the milonga halls too. It's something similar in Russia, but more crude, more powerful, and more dangerous there. A simple careless word gives you years in prison, and if it is found to indirectly contribute to Western sanctions, then it's life in prison. How much worse is it going to get before it gets better?

Amazing connections in that story.

ReplyDeleteIt is a dreadful thing when people can't live freely, speak freely, voice their opinions. A Catalan woman today told me she remembered under Franco, when regional languages and culture were suppressed, that they lowered the blinds in the classroom and sang Catalan songs, but very quietly, so as not to be seen or heard. There are long-lasting consequences to oppression: "And they wonder why we want to be free from Spain", she said.

My dad, who's 83, says there is a lack of tolerance in the world today. He says it's teasy for us here to demonise Russia, talk about the aggression, the invasion of another nation, the lies, the excessive violence, thuggish tactics, the national aggrandisement coming from a man obsessed with not appearing weak - who can't afford to be seen to lose, but who Ukraine and the West can't afford to win. We don't think we've "done anything" to them, which is why we see it as aggression.

But, dad says, see it from the other perspective: Russia sees NATO as a potentially hostile bloc of countries whose border has continually expanded against Russia's. To them perhaps that looks like repeated acts of aggression and certainly a threat.

I am not sure who is right. Personally I don't think invading a sovereign state compares with joining a club but perhaps what is or is not is less the point. Rather, it is understanding how the other sees things that is the starting point for any solution.

I should never try changing the opinion of someone's father, but if you aren't sure who's even right, then perhaps I should remind of a few things about this NATO fearmongering. Most of it is outright lies, like all these tails about "the bioweapons labs of NATO in Ukraine" and "genetic warfare against the Russian people". Most of the rest is exaggeration ... because NATO's expansion near Russian border didn't involve stationing any troops, missiles, etc. offensive weaponry. It was just a way to tell the Russians to not attempt invading if they don't want to risk the whole block's response. One thing, though, was probably NOT an exaggeration ... it was a threat posed by the NGOs and the fledgling civic society to the dictatorship, and the fact that the West gave it some support. So the government set out to eliminate the opposition and all forms of non-governmental civil society - as benign as supports groups for cancer patients - as dangerous stooges of the West and enemies of the traditional values. To be successful, such a crusade against the civic society required an invention of an existential military threat to Russia. That's where the government-fanned fears of NATO found their place.

DeleteBut the ordinary Russians can't escape the poisoned torrent of the propaganda, and its most successful claim is that the Russians have been treated unfairly, and that the rejection and fear of Russia in the West are unjust and unjustified. There is a popular skeptical meme about which I should try translating.

"Если тебя незаслуженно обидели, догони и заслужи"

"If someone treated you unfairly and you didn't deserve it, then chase this SOB and do everything to deserve it".